Bathymetry is the study of underwater depth of ocean floors, lake floors, or river floors. In other words, bathymetry is the underwater equivalent to land topography or hypsometry (the measurement of the elevation and depth of features of Earth’s surface relative to mean sea level).

The depth of Lake Erie has been measured in many places for more than a couple of centuries. However, the measurement techniques have not been consistent during those many years, nor has the there been consistent precision measuring the details. Also, the depth measurements have not necessarily been adjusted for the various lake levels during the earlier years, and attempts to define standard lake level benchmarks had been hindered by the earlier technology and knowledge. It was not initially understood that the land is bouncing back up and at differing rates at various locations after the weight of the glaciers disappeared. This bounce is still happening. Today there is good overall knowledge of the basic contours of Lake Erie’s bottom, but precision is lacking, and as what data there is was not gathered at one time.

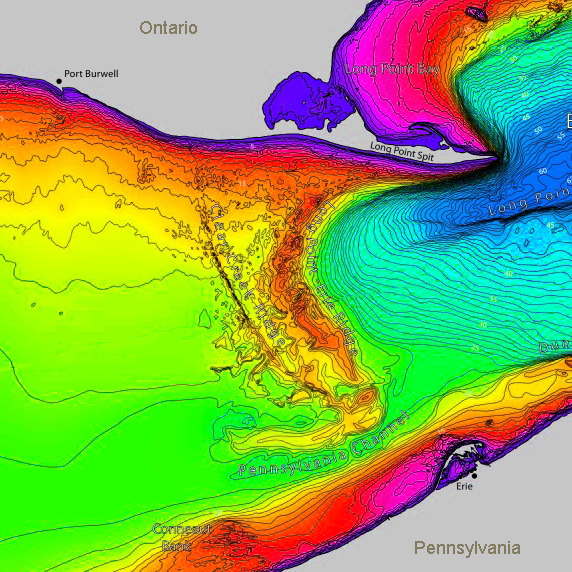

Here is a good overview of the current knowledge of Lake Erie’s bathymetry.

It is guesswork to precisely understand what changes are occurring. To address this issue for all of the Great Lakes, there is currently a bill before the U.S. Congress, The Great Lakes Mapping Act, that has bipartisan support to fund extensive biometric studies of the Great Lakes with a budget of $200,000,000 USD over ten years. If passed, this could provide an excellent reference for monitoring future changes and rates of changes of the lake’s bottom.

In some respects Lake Erie might considered to be a river – about twice as wide as the widest part of the Amazon River and much wider than the McKenzie or the Mississippi. By time its flow reaches the Niagara river, the outflow rate is 5,796 m³/s. The largest single inflow to Lake Erie is from the Detroit River with an average flow of approximately 5,200 m³/s. The discharge from Lake Erie is more than half of that of Canada’s largest river, the MacKenzie River which has a seasonal average outflow of 9,910 m³/s.

Below the surface there is a major ridge that influences the lake’s flow from west to east. It is also an impediment for deep draft ships. The west side of it is called the Clear Creek Ridge and the east side is called the Long Point – Erie Ridge. At the southern end of it, nearer the Pennsylvania side of the lake is the Pennsylvania Channel. Ever wonder why the big freighters are rarely seen from the Ontario side? In part it is because the Earth is not flat, but also it because those large ships use the Pennsylvania Channel. Occasionally, when there are very strong offshore winds coming from the north, the freighters will come into view as they detour to be nearer the north side to avoid the worst of the waves that reach their maximum heights to the south. Even then they will use the Pennsylvania channel.

Based on map by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

NOAA

Do these underwater ridges influence any littoral drift, perhaps acting to redirect the moving sand at or near the bottom either to the south or to capture some of it thereby increasing the size of the ridge and reducing what passes by to Long Point. If so, with the passage of time and accumulating sand, might the sand portion of the littoral drift reaching the Long Point Spit be gradually reduced? Presumably suspended clay and silt would not be impeded to the same extent.